By Miles Layton

Tangier Post Facebook Page

TANGIER, VIRGINIA — Long a part of American history, this tiny island in the Chesapeake Bay has a museum dedicated to preserving and sharing the past, however, Tangier offers more through its “living” history.

The Tangier Island History Museum is a testament to the island’s heritage, past and present.

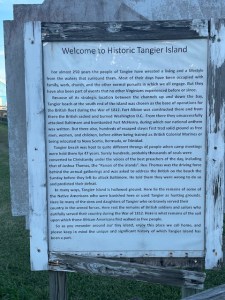

Captain John Smith named the island during his voyage up the Chesapeake more than 400 years ago because it reminded him of Tangier, a city in Morocco.

During the War of 1812, Tangier served as a staging ground for the British fleet for the Battle of Baltimore — an event that inspired Francis Scott Key to compose “The Star Spangled Banner.”

For nearly 1,000 slaves during the War of 1812, Tangier was a fortress of salvation and the place where they took their first free steps. Fort Albion, named after the ancient name for England and Commodore George Cockburn’s flagship, was constructed on the island in 1814.

Generations of watermen have raised families on the island, so the museum’s exhibits chronicle the culture and heritage of their isolated home in the Chesapeake Bay.

“People started digging in attics and in storage sheds and finding all these artifacts and all this stuff that we have in here in the museum. And it’s been a labor of love,” said Andrew Langley, a key volunteer at the museum who is a longtime resident of Tangier. “I mean, every year people find something and thing, ‘how about this for the museum?’ So it’s constantly changing. We have everything represented basically from when the island started back in 1608 all the way to present day.”

Then there’s the oyster-crab — yes, you read that right. The creature is a mix of crab and oyster — crustaceans caught in the Bay by watermen for hundreds of years.

Preserved in a glass case, the oyster-crab is real unlike a unicorn or a jackalope — a mythical animal of North American folklore described as a jackrabbit with antelope horns.

“When our mayor (James “Ooker” Eskridge) caught it in 2017, he published photos on Facebook,” Langley said. “Some scientists thought he was making a ‘Jackalope’ situation trying to fool somebody. And he told them to come look at it. He had it alive at the time in one of his crab floats. And they came and looked at it and researched it and found out that it was real.”

Museum shares stories with black and white photos of Tangier’s past — what it looked like when 1,500 people lived on the island — life then is much the same as it is today.

“I’ve been here about 35 years and what I’ve noticed is that people that come to the island from the mainland and try to change Tangier and try to change things — 100% haven’t lasted, haven’t made it,” Langley said. “One reason is because people just won’t associate them socially and they won’t get that islander bond with them because they think they’re trying to take their heritage and change things. But the ones like myself and several others that have come here, they embrace the community and have taken on the lifestyle.”

Langley continued, “People that move to the island and stay tend to blend in and find out the way people do things on the island by just taking it all in and enjoying themselves.”

Like most places in close-knit communities, no matter whether it’s the Eastern Shore or a holler deep in West Virginia, Tangier’s residents, many of whom come from families who have lived and died on the island for generations, use time to define the two types of people who come to the island.

Langley said people who have moved to Tangier but haven’t been there very long are called “come here’s” whereas longtime residents are called “muddy toes.”

“New people — they’re called ‘come here’s’ for a while, but then after you’re here for so long and you stay and you make it and you got ‘mud on your toes’ that’s when you know, you’re in — a part of the island.”

Like the museum, Langley shared stories about the island’s people who are a special blend of folks who care deeply about their community. Neighbors wave to each other as they move about the island. If you’re walking, Mayor Eskridge and others may give you a ride in a golf cart to your destination.

“Everyone knows each other — Tangier is a place where you can leave your doors open, unlocked,” Langley said.

Old men gather at the marina to talk about politics and fishing. Rather than push colors around in video games all day, kids play together, often biking around the mile or so loop around the island.

“Kids, if you got kids, you don’t gotta worry about those kids because everybody on this island is watching out for them,” Langley said.

Church is a big thing for folks in Tangier because working on the water can be dangerous and living on an island that faces the possibility of extinction because of erosion or climate change is an act of faith.

And then there’s the history of the island that’s tied to Methodism.

In front of Swain Memorial United Methodist Church there is a historical marker dedicated to Joshua Thomas (1776-1853) — a skilled waterman known as the Parson of the Islands who traveled in a canoe called the “Methodist.” Thomas conducted services for British forces stationed at Fort Albion during the War of 1812 and foretold their defeat at Baltimore in 1814.

Past or present, church brings folks together in good times or bad.

“I don’t know if you remember the January blizzard of 2000,” Langley said. “It was about the last couple weeks around 20th January. It had the whole East Coast in its grip from Florida to Maine. It was so bad. Well, my father died down in Louisiana, so I was unable to get there because we had a (Ford) Escort station wagon. So there’s no way I could have been allowed on the road. I couldn’t even get off the island actually because the weather was too bad.”

Langley continued, “So we went to the Methodist church up the road, I said, ‘Do you mind if me and the kids, when they’re having their funeral down in Louisiana, do you mind if we sit here in church? And I’d like to tell them some stories about their grandpa.’ Pastor said, ‘No problem.’ So we’re there and the door starts opening up at different times. And before it was done, we had 35 people sitting in the church with us in a roaring blizzard.

“Snow was coming down, blowing up under the door, but yet they cared enough about us to come and sit with us and hear stories about my dad. For 3 to 4 weeks, my wife didn’t have to cook a meal because of people. And this is still the same way today. When somebody passes away on here or gets injured real bad, gets hurt, we help each other. And this is the thing about the island that you don’t see a lot of the places.”

The Tangier Island History Museum is located at 16215 Main Ridge Road, Tangier, Virginia. The museum typically open from 11 a.m.-4 p.m. Monday-Saturday and noon-4 p.m. Sunday. Admission is $3, free for children under 11, military veterans, active duty servicemembers and Tangier residents. For information, call (757) 891-2374.